Bible Stories Where Jesus Is Funny

For some time, I have been intrigued by the question of whether Jesus was funny. In his teaching, did he tell what we might call jokes, and did his listeners find themselves laughing when they listened to him?

There are manyprima facie reasons why we might suppose Jesus was funny. If Jesus was fully human—indeed, the perfect embodiment of humanity—then we might expect him to be funny since this is a hallmark of humanity. In his 1971 bookA Rumour of Angels, sociologist Peter Berger argued that humour was one of the seven signs of transcendence in human life. And this accords with our own experience—that we often find people who are funny are the most alive, and that there are times when a good laugh can restore our sense of humanity.

And if Jesus is the embodiment of the divine, that might also lead us to expect him to be funny. It has been said that playfulness is the hallmark of intelligence, so we might expect the ultimate intelligence behind the universe to be ultimately playful. We get a glimpse of this in Job 38–41, where God's account of creation does focus on God's power as creator—but also on God's playfulness in the strangeness and variety in the creation.

And there are some direct clues about Jesus' joyfulness, and so we might infer his laughter. The most obvious is in Luke 10.21:

At that time Jesus, full of joy through the Holy Spirit, said, "I praise you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because you have hidden these things from the wise and learned, and revealed them to little children. Yes, Father, for this was your good pleasure."

If someone is full of joy, looks to heaven, and talks of praise, it is quite hard not to imagine this person laughing. Another strong clue comes in the accusation by his opponents (recorded in Luke 7.34 and Matt 11.19) that Jesus was 'a glutton and a wine drinker'. He was clearly thought to be a party animal, and it is hard to imagine this without some laughter being involved.

Despite all this, I think it is fair to say that Jesus is not often described as laughing—there is no equivalent 'Jesus laughed' to the Johannine 'Jesus wept' (John 11.35). And Christian preaching and theology has generally resisted C S Lewis' dictum that 'joy is the serious business of heaven'.

So can we find humour in Jesus' teaching? Can we identify it with confidence, and how might it affect our preaching and teaching? Understanding humour across cultural boundaries is notoriously difficult. A couple of years ago, we went on a short trip to Morocco, and we discovered that Moroccans have quite a distinctive, teasing sense of humour. Having had lunch at a local cafe one day, I went up to the owner to ask if I could pay, to which he replied 'Yes, if you want to!' The teasing humour of our driver on a trip to the desert did not go down well with a Dutch family we were travelling with, who interpreted his joking comments as rude insults! If it is hard for humour to travel from one modern culture to another, how much harder must it be to interpret humour from the ancient world?

In an earlier discussion on this subject, Colin Edwards makes this observation:

Humour is one of the hardest concepts to understand in crossing cultures. The gap from 0AD Palestinian Culture to today is a lot bigger than the gap between German and English. I lived for 17 years in Bangladesh and saw 3 main types of humour: slapstick; people acting out of social position (e.g. a doctor dressing as a sweeper and sweeping the floor); and the Jester figure (e.g. funny clothes, funny voice etc.). Verbal humour and word play was much less a part of the culture. The use of humour in public speaking is also a lot less.

I heard many captivating Muslim preachers, and they rarely used what we would call humour. They happily denounce others and make the opposition look silly, and therefore objects of humour. Jesus did that regularly (e.g. "Let he who is without sin, through the first stone" and "show me a coin". This last one was in the temple, where a coin with a head on it was considered an idol.).

One of the most extensive explorations of humour in the Bible (actually mostly focussing on the New Testament and the teaching of Jesus) isThe Prostitute in the Family Tree by Douglas Adams (not the same as the author ofHitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy—as he himself comments in the Amazon reviews!). Adams begins by looking at the humour in Bible stories, and describes them as 'grandparent stories' rather than 'parent stories'. Parents want their children to behave, and so often tell serious stories with a moral point. But grandparents can afford to be much more honest, and as a result humour and irony emerge more commonly—and that is the usual approach of Bible stories. Christian readers often try and impose a serious morality on stories which resist such readings. As an example, Adams considers the genealogy in Matthew's gospel, with the ironic presence of Rahab the prostitute, who gives the book its title. Hie notes the comedy in the contrast between the (expected) good characters listed and the (probably unexpected) bad ones—and offers an interactive, dramatic retelling in order to enable congregations to engage with the contrast, which is sure to lead to lots of laughter.

Adams explores different aspects of the humour of Jesus' parables in three chapters, before looking at the absurdity and humour in some of Jesus' miracles, and humour in Paul's letters. His examples illustrate some of the challenges in looking for humour, but also the potential in both the gospels and Paul's letters.

The most obvious demand is knowing something of the historical and social context. Early on, Adams explores the so-called parable of the prodigal son in Luke 15. Most of us will have realised the cultural significance of the younger son being reduced to looking after unclean pigs, and we might be aware of the expectation that, on his return, he would prostrate himself before his father, who would customarily have remained at a distance. But did we realise that the expectation would have been for the elder son to act as reconciler—a task that he signally fails in? Adams also demonstrates the need for a careful reading of the text itself: did we notice that the younger son quickly drops his plan to be a servant when he sees the welcome that he receives?

Adams also notes the surprise of many of Jesus' economic parables, which draw on seemingly unethical practices to illustrate the kingdom of God. Should a good Jew be happy with speculating and investing the money entrusted to him in the parable of the talents? What is virtuous about the cunning steward who writes off the debts owed to his master in order to curry favour with those from whom he will later seek employment?

But these demands also illustrate how precarious it is looking for humour in another culture. Adams sees both insight and incongruity in Jesus' parable of the kingdom as a mustard seed (Luke 13.19, Matt 13.31). The mustard plant grows quickly—but it also dies quickly, being an annual, and is something of a contrast to the image of a cedar of Lebanon, a much more common illustration in the Old Testament of what God is doing. Is Jesus really wanting to talk of the kingdom as something transient that doesn't last? Or do we need to focus on the main point of the parable as Jesus tells it—that the kingdom starts with small things, and grows surprisingly quickly and organically when we might not expect it?

The use of cultural insights can also be precarious. Adams discusses the parable of the neighbour who has a night-time visitor in Luke 11—which I recently preached on. Here Adams disagrees with the cultural insights of Kenneth Bailey, and he sees both the timing of the demand at midnight, and the quantity of the demand (three loaves rather than the one that is needed for one guest) as being absurd. I think it is more persuasive to see this as something entirely expected in a culture where people traveled in the evening, rather than in the day, and where hospitality was a prized value. What is more amusing is the comparison of God with a grumpy neighbour, reluctant to help, whom we are disturbing from sleep with our constant, untimely requests!

Adams omits reference to what I think is perhaps the greatest failure of humour by biblical commentators—in relation to Jesus' comment in Matthew 19:23-26, Mark 10:24-27, and Luke 18:24-27 that 'it is easier for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven than a camel to go through the eye of a needle'. Cyril of Alexandria suggested that the word translated 'camel' should be read as 'rope' (kamilos instead ofkamelos), and mediaeval commentators speculated that there was a small gate in the wall of the city called 'The eye of the needle' through which camelscould pass, if only they knelt. Both attempts avoid the absurd humour of Jesus image, which was captured rather well by J John: 'You couldn't get a camel through the eye of a needle if you passed it through a liquidiser!'

Adams does include one fascinating observation about humour in Paul's letters, where he sees 1 Cor 11.34–35 as a Jewish objection to Paul's teaching, which he then ridicules in the verses that follow—some 20 years before Lucy Peppiatt Crawley argued that same on other grounds.

I wonder if what Adams is doing is less highlighting the humour in Jesus teaching and rather highlighting the underlying paradox, absurdity and surprise in his teaching about the kingdom of God. Most humour depends on leading us down a particular line of thought—only to surprise us with something quite different at the end of it. And this is essentially the truth of the good news of God's love. When we look at God's good intention in creation, when we consider all the ways God has provided for and blessed us, and we then see what we have done with the world and the way we have mistreated and dehumanised our fellow creatures, we can see where this story should probably end. But the good news of God's costly redemption comes as a surprise ending—even an absurd one which we could not reasonably expect. What Adams does is alert us to this absurdity throughout the New Testament, and encourage us to make the most of it.

If Jesus did indeed laugh, use humour, and make his listeners laugh even as he challenged them, shouldn't we do the same?

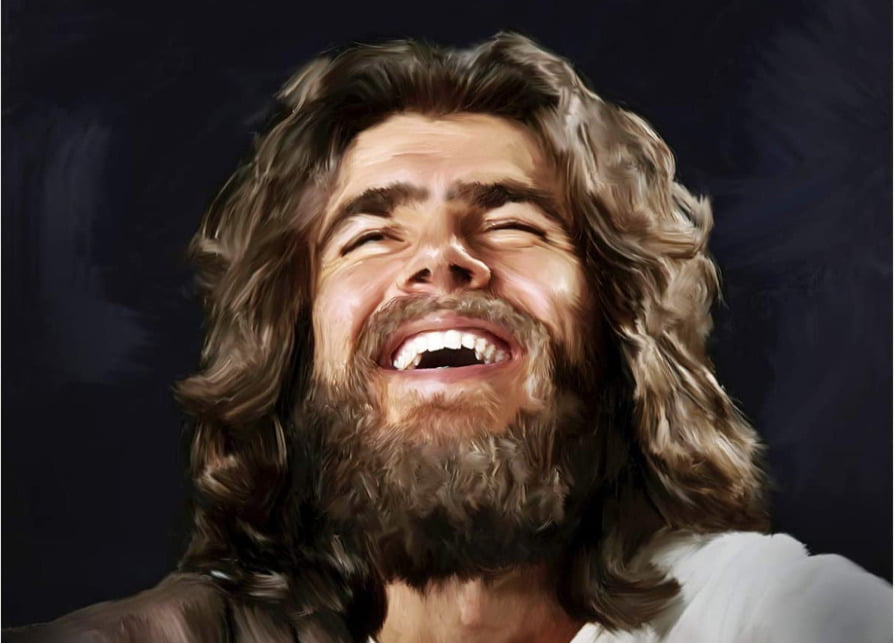

The picture above is by Deb Minnard, and you can order a print of it online. A previous discussion of this subject was posted in 2018.

If you enjoyed this, do share it on social media (Facebook or Twitter) using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo. Like my page on Facebook.

Much of my work is done on a freelance basis. If you have valued this post, you can make a single or repeat donation through PayPal:

Comments policy: Good comments that engage with the content of the post, and share in respectful debate, can add real value. Seek first to understand, then to be understood. Make the most charitable construal of the views of others and seek to learn from their perspectives. Don't view debate as a conflict to win; address the argument rather than tackling the person.

Source: https://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/did-jesus-laugh-was-he-funny/

0 Response to "Bible Stories Where Jesus Is Funny"

Post a Comment